How Long Should You Hold Your Net Net Stocks?

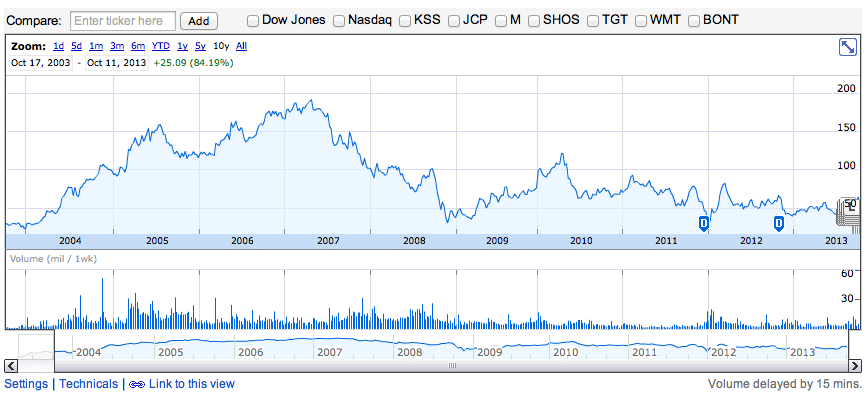

I finally sold Sears, completing my transition to a pure net net stock investor. During the time that I held the stock I watched it spike, and then sink well, well, past my buy price. Sears has been the single most painful investment I've ever made.

Long Term Investing

I should have known better -- and I guess deep down inside I did -- but my own psychological denial kept me from looking at the situation objectively. It kept me from taking a cool, calculated, stance towards the stock and ended up costing me thousands of dollars.

A lot has been written on mechanical investing but one of the earliest pieces of advice that I've read was from Benjamin Graham. In one of his volumes of security analysis Graham advises investors to keep from holding net net stocks for too long, advocating a 3 year cap on holding periods. A lot can happen in 3 years and if an investor holds on to a stock for much longer than that, he risks giving up significant opportunities that would otherwise prove far more profitable. A stock can go unrecognized for years. While you're sitting on your hands waiting for the price of the stock to advance to its fair value other cheap stocks are busily advancing to their own fair values and the opportunity cost decision you've made slowly erodes your returns. It's easy to think that the turnaround you've bet on is just around the corner but this kind of thinking can suck you into a dead stock for years.

The Big Question: How long should an investor hold onto stocks for?

Or, more clearly: how long should a net net investor hold onto his picks for? Different investors with different strategies will come up with different optimal holding periods -- something to be expected -- but with net net stocks there's a few more options. While Buffett hopes to hold onto his purchases forever, the same technique wouldn't work as well for deep value investors. Buffett invests in great companies with secure competitive advantages, something net net stocks seriously lack. This is what makes Buffett's picks so compelling. An obvious consequence of this is that investors shouldn't hold forever and by extension the technique of selling a portion of your holdings once the stock has advanced and letting the rest ride is probably a bad idea, as well. One advantage of this technique is that investors would be able to participate in the gains realized by a stock that rises well past NCAV. Trans World Entertainment is a good example of this. The issue here, though, is that an investor is basically pitting a different type of value strategy against Graham's net net stock strategy -- a bet that will likely cost the investor long term. Few strategies do better than Graham's net net stock strategy so opting to hold on to a stock so it can realize some other price based on some other value metric essentially means shelving Graham's more profitable strategy for one of his less profitable strategies. If this happens too often then returns are guaranteed to suffer.

Fill your portfolio full of high potential, low risk, net net stocks. Click Here.

If sticking to a NCAV stock strategy is the best course of action, then the the obvious choice is to sell them when they become fully valued on a NCAV basis. What about the ones that are taking a while, though?

Studies Suggest That...

Of the studies that I know of that look at net net stocks, two ("Net Current Asset Value, Financial Distress Risk, and Overreaction" and "Testing Benjamin Graham's Net Current Asset Value Strategy in London" by Xiao & Arnold) look at holding periods. The conclusions they draw are very straight forward -- shorter holding periods are associated with better overall performance.

The first specific takeaway of the pair of studies is that if you hold past two years then your portfolio will still increase in value by a meaningful amount but your average returns will fall. Past two years, your compound average rate of return drops significantly. Essentially, the advantage you have of choosing a NCAV investment strategy is completely nixed -- you might as well just chose a low price to book or low price to earnings strategy for anything past 2 years.

The other key takeaway is that holding for only a year has a slight advantage when compared to holding for two years. While the impact to portfolio results weren't as clear as the negative affect of holding for more than two years, the difference was notable. While investors could expect to earn 31% over a 1 year holding period, in the Xiao & Arnold study, their compound return would be slightly higher, at 32.5%, if they held for two years. On the other hand, a one year holding period in the "Net Current Asset Value, Financial Distress Risk, and Overreaction" study would have netted a 32-34% return compared to a 25.25-27% compound return if held for two years. That extra 7% would certainly add up for investors over time.

So, the answer is one year holding periods?

Possibly. Real world circumstances may make this holding period strategy very difficult, though, and an investor should consider all facets of his investment strategy when deciding on a holding period. During market dips it can be easy to load up on net net stocks. The same cannot be said about market peaks, however, making a one year holding policy problematic. Practical implications come into play. Should an investor chose a whole new crop of investments or completely change his or her holdings? Should an investor ignore quality when making purchase decisions? What about debt level, insider ownership, or other key considerations on an investor's checklist? If an investor invests in the best crop of net net stocks as part of his original portfolio then rebalancing would mean trading in great picks for good picks, or worse.

None of this even gets at what should be done when a stock reaches full valuation before a year is up. Keeping it in the portfolio may see the stock crash back down to earlier levels and selling the stock without purchasing a new stock would be a definite drag on performance.

I think it's pretty clear that a one year holding period is impractical but that doesn't mean that an investor should give up rebalancing after a year's holding period. If enough net net stocks are available, then investors can take a look at what else is out there after a year's time. Maybe another stock looks like a better pick or perhaps the classic Graham investor has the opportunity to buy a stock at a much cheaper price -- something I wholeheartedly recommend.

If a one year checkup leading to improvements in a portfolio's quality is a good thing, what should an investor do with the stocks of companies that haven't seemed able to turn themselves around yet so still sit there at bargain basement prices? Well, if my Sears example is anything to go by then it's a mistake to hold on to a company with deteriorating fundamentals just because you think the turnaround is right around the corner. It took me a 66% loss and 8 YEARS to admit that! If I had of just sold after a certain arbitrary cut-off then I still would have been out a large amount of money but at least I could have recycled what I had left into deeply depressed value stocks and made that money back. Instead, I'm stuck trying to do that 8 years later... which is fairly devastating.

So, an investor has to chose some curt-off period or possibly face my same fate. Sure the stock could go up right after selling that but, due to the nature of net net stocks, a net net stock could skyrocket in price at anytime after a bit of good news. Add to that how much more likely another company may be to turn around and the consequences of holding on to these failing turnaround stocks for years (essentially, that your portfolio becomes nothing but failed turnarounds) and a pretty strong case can be made. It's best to just cut your losses and start over.

So That's It

The best holding period is not a strict holding period at all. Investors should look at replacing stocks in their portfolio no less than once a year and do so if anything else seems a better bet. They should also sell stocks that become fully valued and then purchase new stocks -- no surprise there. After three years of a stock not performing an investor should just replace the stock, with one important caveat: if a company's NCAV is rapidly increasing then so is the investor's profit potential in which case it makes sense to keep the stock. If all of that value gets realized at some point then it really doesn't matter when... so long as the value is increasing at a good clip. All this seems intuitive to me, in any case. I just wish I would have sat down to think of it earlier -- at least that would have kept me out of Sears.

One of the biggest issues with net net investing is finding investment candidates. You can solve this problem by signing up for full Net Net Hunter membership. The money you could make off of even just one international net net stock would be enough to pay for full membership access for years. …and right now we have over 400 stocks to look at.

Not ready for full membership? That’s fine. Just sign up for the free net net stock essential guide in the box below this article. No commitment, no obligation, and we keep your email address 100% confidential. Don’t wait. Sign up now so you can start making over 25% annual returns through net net stocks.